Why Do Hipsters Grow Mullets?

by Patricio Maya Solís

Pop Culture Critic

patriciomaya.com

Time magazine's LightBox blog was one of the first publications to cover Steven Rubin's new drkrm show, Vacationland. Some of the blog's readers, apparently Mainers, showed concern about the image of rural Maine put forth by Steve Rubin's photos. More to the point, they thought Rubin made rural Maine look like a shithole. Here are four of the strongest reactions: "Good Lord, way to give Maine a black eye." "So these photos will be posted in LA where hipsters and elitists can mock Mainers? Are there any plans to bring these to Maine?" "These photographs, while beautiful, depict rural Maine as being full of hopelessness." "I grew up in Somerset County, graduating high school in 1982, when some of these photos were taken. Yes, these are beautiful 'raw' images of the subjects. But this is only a representation of one family and one sector of the region. Please don't think that all of central Maine is this desolate. We have beautiful spots too..." Look, nobody wants his hometown depicted as some type of wasteland. That's understandable. The thing is, comments like the ones above miss a huge part of what Vacationland is about. Sure, the poor, "trashy," rural elements are all in the images. And they are important. They capture the everyday reality of some people who live under certain conditions and are part of a certain subculture. These people are not from Beverly Hills or downtown Los Angeles. But that's not, by far, the main part of the show. In a sense, Vacationland has little to do with Elvis posters, junkyards and shotguns. It has more to do with naiveté, familial love and personal vigor. These are hardly negative ideas. Rural Mainers can rest assured. Nobody --no one worth a damn in any case-- will think of rural Maine, central Maine, or whatever, as a shithole because of Vacationland. Those who do are not necessarily hipsters or elitists. They're just superficial. And superficial people come in all forms.

February, 29, 2012. Socialitelife.com catches pop star Rihanna coming out of a seemingly posh London establishment. Seventeen photos of the "event" are posted online. Rihanna is wearing a faded denim shirt, an oversized trucker hat, studded white hot pants, tacky thigh-high leather boots, purple lipstick, dark sunglasses, three cheap-looking necklaces, and gilded hoop earrings. Under her left earring there's a neck tattoo with the words "rebelled fleur," written in the kind of cursive handwriting formerly associated with jail gangs. Her bleached, frizzy hair is kept in a haphazard ponytail, under which darker roots are not only shown, but flaunted. A tall man in a suit, perhaps a bodyguard, stands behind her at all times; fans stand in front. The caption by the photos reads, "Rihanna Goes White Trash Chic."

Picture this craziness. A Barbados-born singer is visiting London dressed like a poor-rural-American (or what some style advisor or clothing designer imagines poor rural Americans look like). The security guard (or friend) on the other hand, is wearing a blue suit. The fans are wearing regular clothes too. Only Rihanna, the star, looks "trailer park chic," "blue collar couture," or whatever. It's just fashion, sure, but thinking of this trend as a mere fashion style doesn't do justice to its wide reach. Fashion is the focal point, but poor-rural-America-inspired culture has already bled into areas like television, music, literature, interior design and even architecture. It's impossible to pinpoint the exact time when the trend went mainstream. It goes back to at least the early 2000s. As with many "edgy" trends, it probably started within a few creative clusters and then caught on with the wider public, until eventually, clothing corporations got hold of it and helped globalize it. Seeing kids today walking around the streets of Tokyo or Sao Paulo dressed as struggling rural Americans would be the most normal thing, even if they, as the Nirvana song goes, "know not what it means." Talking about Nirvana, the same happened with grunge in the 90s. Old jeans, boots and faded flannel shirts were the staple style of the Pacific Northwest working class, including alternative musicians and fans. After the local music scene became famous, the grunge look went global, even couture, before it finally faded away.

As the Rihanna photos show, the "white trash" look has already spread far beyond counter cultural clusters, so it can't last too much longer. For now, though, it's still around. This is an ad for what sounds like a wonderful club in Florida: "Redneck cool. Trailer-park fabulous. White-trash chic. Blue-collar vogue. Whatever you wish to call it, it is hip and it's fun with a downtown vibe. With great promotions and parties, live music, 32 huge TV's, a full delicious menu and a ton of cool people to meet every day, Whiskey Tango gives you something to do and a place to hang 7 days a week!" Whiskey Tango is code language, of course. Whiskey stands for white and Tango for trash. Going trashy is a commercially attractive model. In 2011, New Times Magazine voted Whiskey Tango "best bar" in Broward and Palm Beach.

Corporations also go nuts for seemingly authentic cultural trends. But when a corporation's branding apparatus grabs a hold of a cultural trend, it goes all out, while somehow staying seamless. Levi's 2010 "Go Forth" campaign, handled by famed advertising agency Wieden + Kennedy, comes to mind. One TV ad shows working class youngsters walking around a struggling rural town. Fireworks go off as a rare wax cylinder recording of Walt Whitman reading his poem "America" plays in the background. Yes, the real Walt Whitman reading from Leaves of Grass is featured in a Levi's ad with the sole purpose of bestowing authenticity upon a brand. Not only that, it was also a way to honor the brand's so-called birth right. "Shot on location in Braddock, the campaign features a dozen residents of diverse backgrounds dressed in Levi's® Work Wear Collection for fall," a Levi's press release said. "Work wear is Levi's® birth right."

Top to bottom examples of rural-poor-inspiration abound; think Ed Hardy, Megan Fox, Kid Rock, My Name is Earl, and Trailer Park Boys. But street level life shows how assimilated the trend has become. Things like cheap beer, trucker hats, mustaches, wife beaters, beards, greasy hair and even beer bellies are worshiped (ironically, but worshiped nonetheless) in many non-poor, non-rural quarters. Some of the most sophisticated women in Silverlake, for instance, will not go out on a date with a guy unless he has a broken tooth and is wearing a Lynyrd Skynyrd T-shirt with cut out sleeves. A case can even be made that some Americans will not vote for a politician unless he or she is "down home."

Hinterland: "A region remote from urban areas; backcountry. A region situated beyond metropolitan centers of culture."

The American hinterlands have become precious because they are fading. They are fading because that's the way of the country; the way of development, growth, expansion, late capitalism, whatever you want to call it. Someday this vast continent will be one giant asphalt block, swarming with urban or suburban dwellers. In this sense the American hinterlands --though one imagines the same thing is happening in China and Russia-- are precious in the same way that dying languages are precious. Dying languages need to be recorded and studied because they present a unique way of looking at the world, a different filter. Dying subcultures, like the one shown in Vacationland, do too. This is particularly true when, like here, they're honestly captured. That said, in his best photos Steven Rubin goes beyond documentation. He reaches intimacy with his subjects by treating them like family. In that sense, Rubin comes closer to Richard Billingham taking photos of his own alcoholic father and obese mother in the photobook "Ray's a Laugh" than to Dorothea Lange recording the plight of poor Americans for the Farm Security Administration during the 1930's. In Billingham, tenderness cancels out much of the judgment; the photos turn your stomach and warm up your heart at the same time. The same is true of Vacationland.

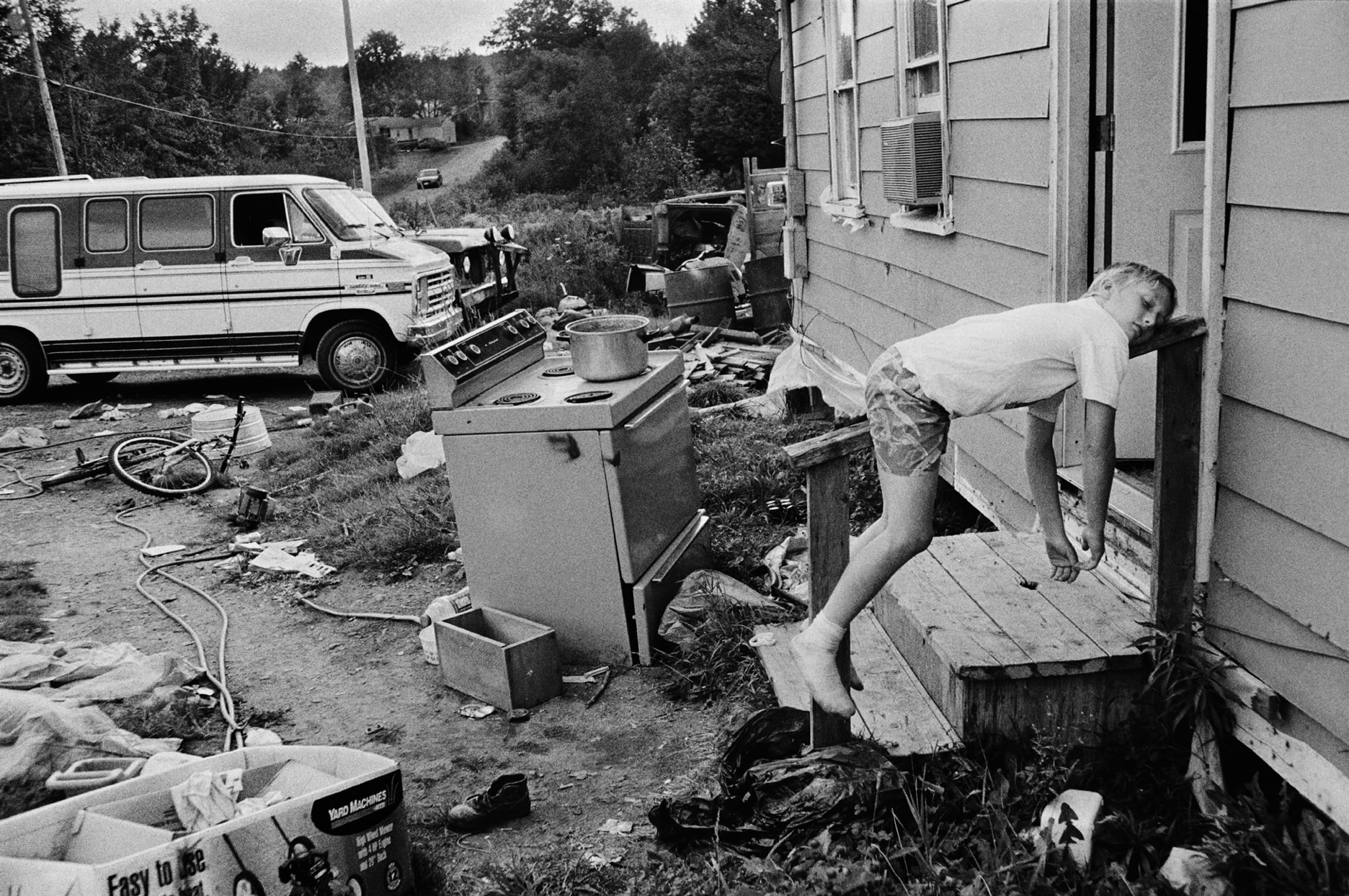

Steven Rubin Adam waiting on his mom to come home 2001

Stomachs are turned by the terrible living standards. But what warms up the heart? The raw poetry! Well, not really. Of course many of Rubin's images are beautiful. The most beautiful one is "Adam Waiting on His Mom to Come Home." Asleep on a stair's handle like some type of exotic bird perched on a branch, Adam's little soul is like a million miles away, floating above the front yard junk (and all the socio economic crap that junk entails). But even so, lyricism is not Vacationland's most salient feature. The idea of longing is. Not the subjects' longing. Polly with the "born to die" tattoos, Tracy with the cat, Rena and Everett under the Elvis poster, Laura Ann with her dad and rifle, and Ernie with his wheel, couldn't care less about you and me. We are the ones in a gallery staring at frozen frames of apparently worse off strangers. Vacationland can reflect back our own cultural longing. That's what's neat about it.

Take "Celebrating Christmas Night Out on the Frozen Bog." These four might not be the most successful or handsomest of men. They are ragged (really ragged, not "trailer trash chic" ragged) and quite possibly smelly and drunk. Two of them are drinking a brand of beer that's quite possibly not Stella Artois. The two on the left look utterly relaxed; the two on the right, fucking blissful. In their crazy abandon they look like wasted teenagers at a punk rock concert. Not too many urban or suburban men in their 50s or 60s (or any post-college age really) can pull this off. Many wish they could.

Steven Rubin Celebrating Christmas night out on the frozen bog 1992

Steven Rubin Lucky gets a Christmas cut 1992

Then there's "Lucky Gets a Christmas Cut." The woman in the Santa hat might not be the best hairstylist in the world. And the wall art isn't precisely Gagosian Gallery material; well, you never know. The point is, this might not even be an actual hair salon. It's probably somebody's house. But three adults are engrossed in the action. It's just a haircut, but look at their faces. They may as well be watching the NBA finals. The man getting the haircut would be right to consider himself the most appreciated man alive. Plus, every person in that room knows each other's name and even what each one likes to have for dinner. You can almost see fraternity linking these people like a pink ribbon around a Christmas gift.

Steven Rubin Hanging deer 1994

In "Hanging Deer" we learn that the man in the photo, or somebody in his circle, killed that poor animal. The deer could have, and should have, been spared. But if all cultural judgments are put aside, a silent vigor comes through. The vigor is not so much in the photo itself, but in its context. The story surrounding the photo is full of adventure, rituals, and a deep connection to the land. Also, there's a sense of real accomplishment. Real blood, real rifles, real killing. It's the opposite of, for instance, Facebook reality. There's no physical detachment in Vacationland's world. To be up by that dead deer, you need to trudge through the cold mud, get on your knees and pull that trigger. Then you need to drag the animal to the truck, drive it home and hang it from a branch. No password or browser will ever grant you access to that reality.

Why does Rihanna wear a trucker hat around London? Why is a Florida bar called Whiskey Tango? Why does a Levi's ad display shoddy Pennsylvanian houses? Why do hipsters grow mullets? The short answer: because terrorists don't attack trailer parks. The long answer: go take a look at the photographs.

essay copyright © 2012 Patricio Maya

images copyright © Steven Rubin

VACATIONLAND

Photographs by Steven Rubin

April 28 -May 26, 2012

drkrm

727 S. Spring St

Los Angeles CA 90065

drkrm.com